- Covid-19 shutdowns are a huge deflationary shock for the world economy – but a temporary one

- The fiscal and monetary response is of unprecedented size, and will not be withdrawn quickly, even after the pandemic ends and normal consumption patterns resume

- We are in for an inflationary shock later this year or in early 2021

- This is probably the end of a four-decade period of falling inflation and interest rates

- Inflation assets and hedges are cheap, as the market does not fear inflation at this point

As cities around the world grind to a standstill, thousands of airplanes are grounded and factories shut down, one can not help but fear for an economic meltdown as covid-19 spreads. Many companies in the service sector are facing bankruptcy as revenues collapse, while countless others decide to shutdown production because supply chains are disrupted or because demand for their products evaporated overnight. Millions face unemployment. The world economy is being hit by an unprecedented deflationary shock as one city after another is being put on lockdown. The equity market recognized as much when it went from record highs into a bear market in the space of three weeks.

Without a strong response from the authorities, another great depression would indeed become a possibility, as the viscous cycle feeds on itself. However authorities around the world have promised to literally do “whatever it takes”, to save the economy from a collapse. Indeed, the measures being put in place currently are only comparable war-time deficits 75 years ago. The initial impact in the 2nd quarter of 2020, will surely be deflationary as the magnitude of the demand collapse will eclipse the worst moments of the Global FInancial Crisis (GFC) in 2008. However as the mandatory quarantines come to an end, and we return to work, the trillions of dollars manufactured by central banks and swiftly disbursed by governments, will have a lasting impact on the economy. Prepare for inflation.

Bull markets end with a bang

The most important bull market of our lives was in government bonds. I started in June 1981, when the Federal Reserve Board led by Paul Volcker raised rates to 20% in order to combat inflation. Long-term bonds had yields in the high teens, while mortgage rates were in the 20% range. Financing assets, companies or real estate was prohibitively expensive. Even in real terms interest rates were high as inflation averaged 13.5% in the US in 1980 – the year it peaked – around 6 percentage points lower than prevailing (nominal) interest rates.

The following four decades have seen an extraordinary period of disinflation and falling interest rates. Although there was the occasional cycle of rising rates lasting a few yrears, the trend was unmistakably down. Indeed, rates have fallen to zero and even slightly below in recent years. The overnight interest rate at several major central banks is negative. Most international 10-year government bonds trade with yields in the -1% to 1% range (US, Germany, UK, Japan, Australia, Sweden). What a dramatic change from the high teens and low %20’s in forty years ago!

Real rates (nominal interest rates minus past or projected inflation) are negative across the world with few exceptions. In the US inflation averaged 2% in the last ten years, while the ten-year government bond currently yields 0.7%. It is hard to find a worse starting point for an investment in fixed income securities. If inflation were to be higher than the past 2%, then the real loss, could be significant.

And higher inflation is what a lof of policy makers have been wishing for. Central bankers and economists have lamented subpar inflation readings, as it limits the effectiveness of monetary policy. In practical terms, nominal interest rates can not fall much below zero on a bank account, as people would start withdrawing funds from the banking system.

Just as interest rate have fallen to record lows and inflation expectations hit rock bottom, authorities are about to unleash the most aggressive fiscal and monetary stimulus since World War II, or maybe ever. In the space of a couple of weeks governments have deployed huge amounts of fiscal stimulus while central banks promised to fund these projects with freshly electronically minted currency.

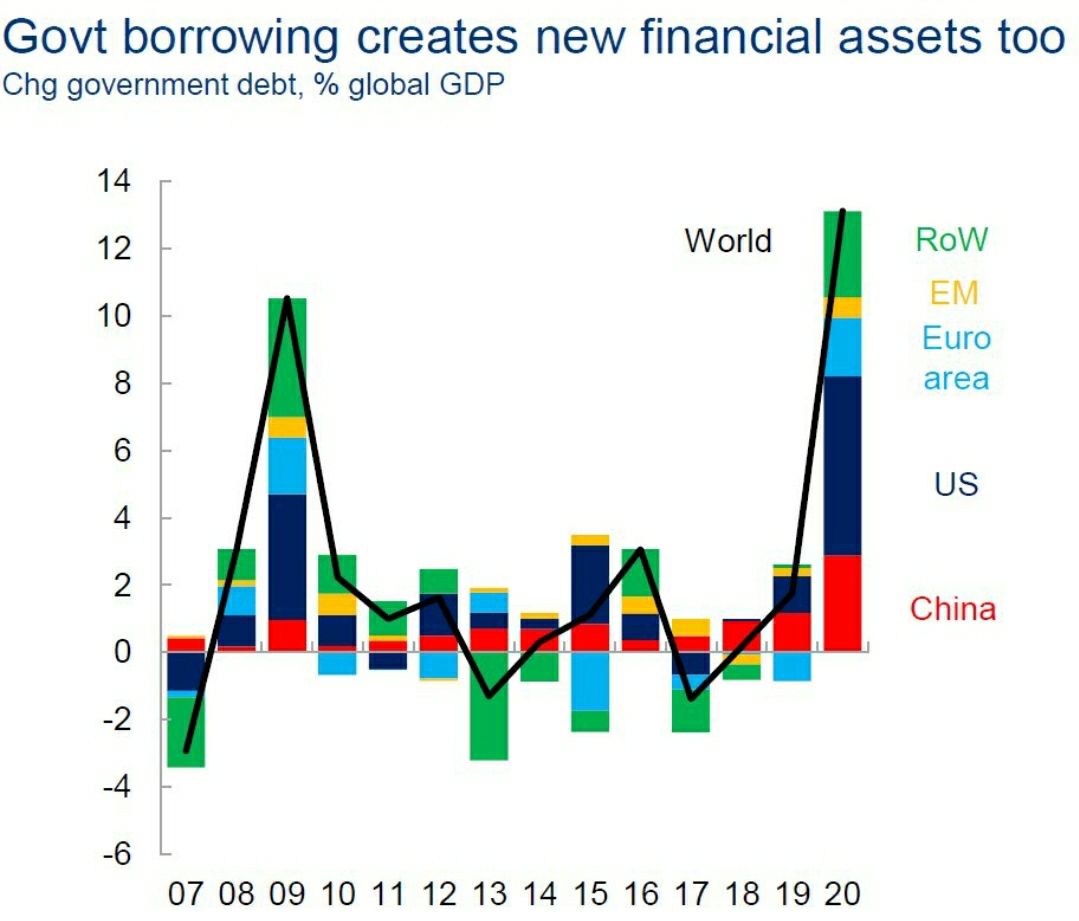

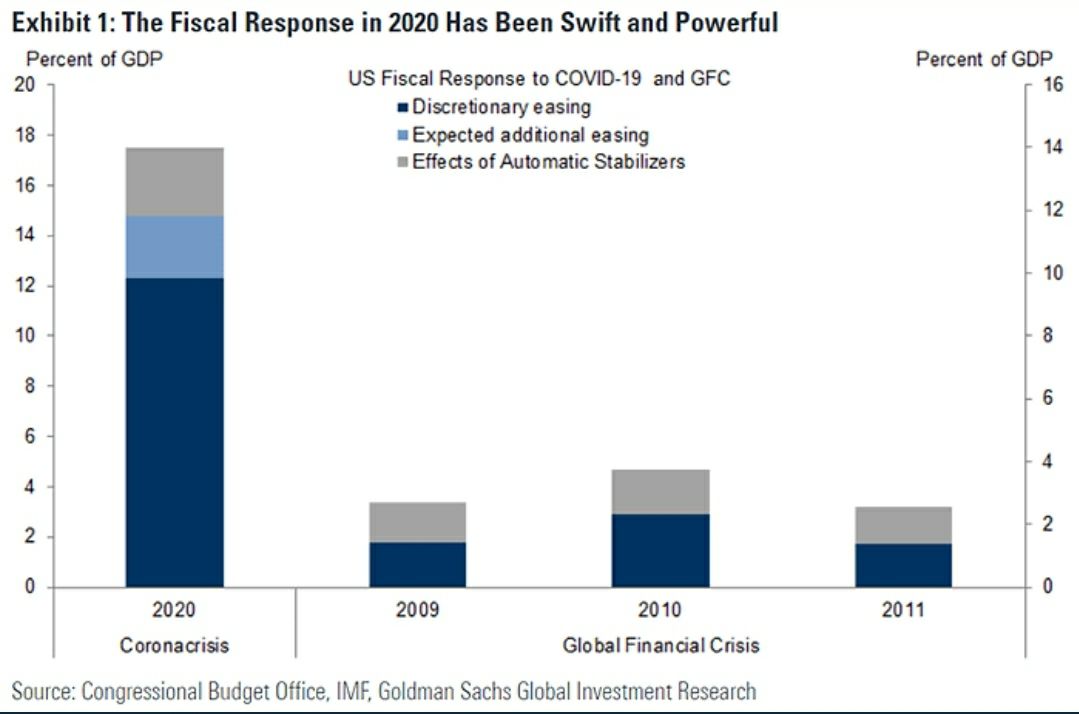

The cavalry arrives

Just as the equity market entered a bear market in a record short time, policy makers have mobilized unprecedented resources in response to the economic fallout. Within the space of a month, Australia has released two stimulus packages (the 2nd almost four times bigger than the first), Singapore has confirmed two packages worth 11% of GDP, Japan has submitted the “biggest ever” economic package, while Germany has given up on fiscal prudence by abandoning the balanced budget rule. Even emerging countries, despite being hit be a wave of capital outflows in recent weeks, have disclosed huge fiscal packages.The chart above is showing very conservative estimates not including loan guarantees and other elements. 10% deficits will the norm in 2020 and probably beyond as every government is breaking records in terms of fiscal largess. In the US, the usually dysfunctional congress, prepared the largest fiscal stimulus in modern history. Around US$2 trillion will be spent on additional unemployment benefits ($260bn), cash handouts to Americans ($250bn), helping large firms and states ($500bn) and saving small and medium enterprises ($350bn). TS Lombard economist Steve Blitz projects a US fiscal deficit of 14% – highest deficit since 1943 – while others estimates are higher still. The measures announced thus far will eclipse the stimulus delivered in 2009/10 during the Global Financial Crisis.

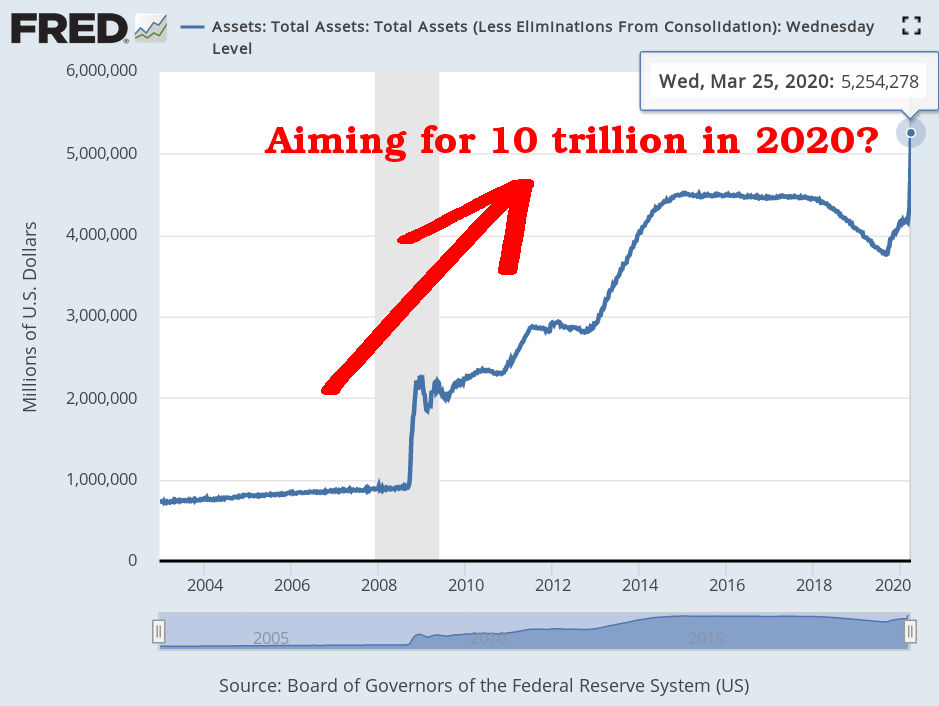

Central banks have been doing their part in fighting the crisis. Interest rate cuts have been followed by record quantitative easing programs (creating money to purchase financial assets). The Federal Reserve is buying a range of assets (including private sector debt) along with treasury bonds, while the European Central Bank, Bank of Canada, the Reserve Bank of Australia and others are also conducting such money-printing operations in their markets. Interestingly, this time even emerging markets have joined the party. Philippines, Colombia, Poland and South Africa have begun buying government and private sector bonds on secondary markets.

Loose monetary policy in combination with loose fiscal policy is a powerful mix. Combine Central bank money printing with cash handouts by governments, and you get what economists call “helicopter money”. It’s a solution put forward by Ben Bernanke amongst others, for fighting deflation.

Bailouts – then and now

During GFC in 2008/09 a handful of developed countries had a go at quantitative easing, and also used the public balance sheet to save the banking sector. However in comparison to 2020, these will have been a timid experiment. Bailing out main street (rather than Wall Street) will be much more inflationary. The approach is to go BIG, bring out the biggest monetary and fiscal bazooka we can. If it’s not enough then do more if necessary. Do more just in case – elections are coming by the way.

With interest rates for the United States being at ZERO, this is the time to do our decades long awaited Infrastructure Bill. It should be VERY BIG & BOLD, Two Trillion Dollars, and be focused solely on jobs and rebuilding the once great infrastructure of our Country! Phase 4

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 31, 2020

Four decades of falling inflation, and subpar inflation since quantitative easing started in 2008, has made many feel relaxed about inflation risks. After unsuccessfully trying to engineer higher inflation, for some time, few policy makers oppose these measures. If inflation were to rise a bit as a result of this stimulus, would that necessarily be such a bad thing?

However inflation is not a linear phenomenon, and it might be impossible to gradually move it from 1-2% to, say, the 3-4% band. Once it starts rising, it might rise a lot. Another factor that will make this episode different from 2008/09 is limited spare capacity in the industry. Corporates invested heavily during the cycle preceding GFC and were left with considerable spare capacity. They will reach full capacity sooner this time around.

Markets in times of covid-19

The change of mindset and this unique event are creating conditions for the long-term inflationary trend to reverse. What are asset allocation implications and what are indicators bear watching for confirmation that the move has started?

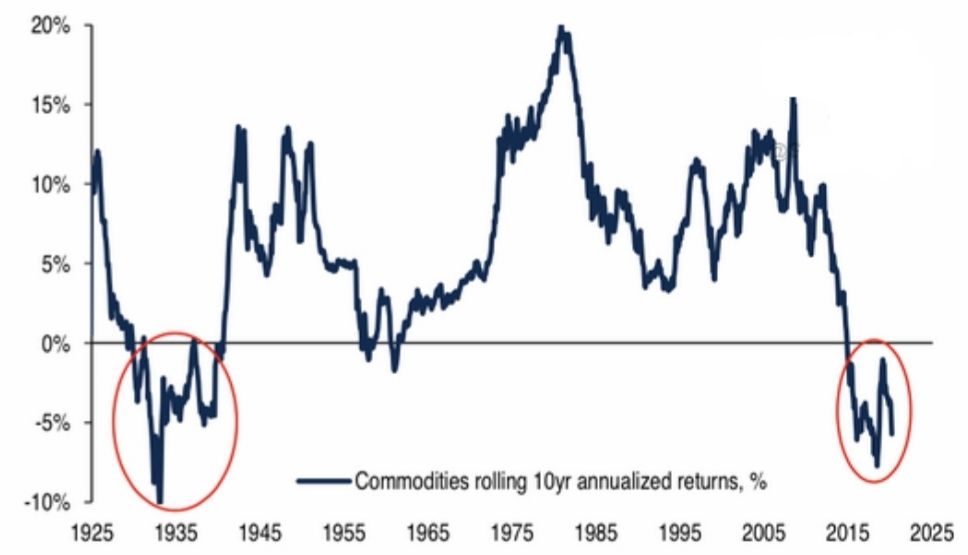

For four decades interest rates have been falling and financial assets (bonds and real estate in particular) have been rising. Commodities have had ups and downs, but without a doubt, the last decade has been the worst in a century (see chart above), comparable the great depression. With inflationary policies being applied around the world, we should see a turnaround in this space. An obvious commodity to watch for signs that inflation is building and fiat currencies are loosing value is gold. Copper is more linked to economic activity but also important barometer (currently around the $2.20/lb).

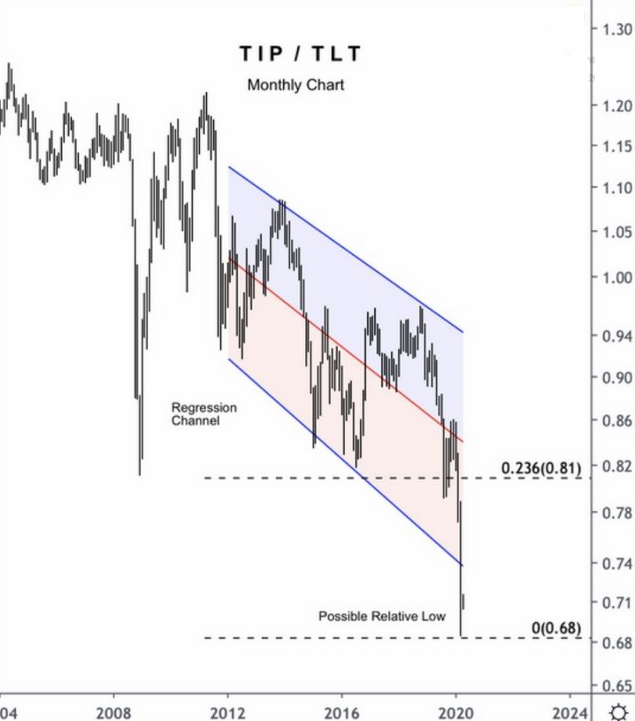

The relative performance of inflation-linked bonds to normal (nominal) bonds is an indicator of deflation/inflation expectations (here proxied by the ratio of two ETFs: TIP and TLT). Currently the market is pricing deflationary gloom – justified by the lock-downs and hit to GDP – but it should give way to a more inflationary period.

Another indicator worth watching is the steepness of yield curves. Yields further out (10 years, 30 years) should start pricing some inflation risk. A ratio of gold to bonds should by rallying if these inflationary policies are successful – the current price action is encouraging:

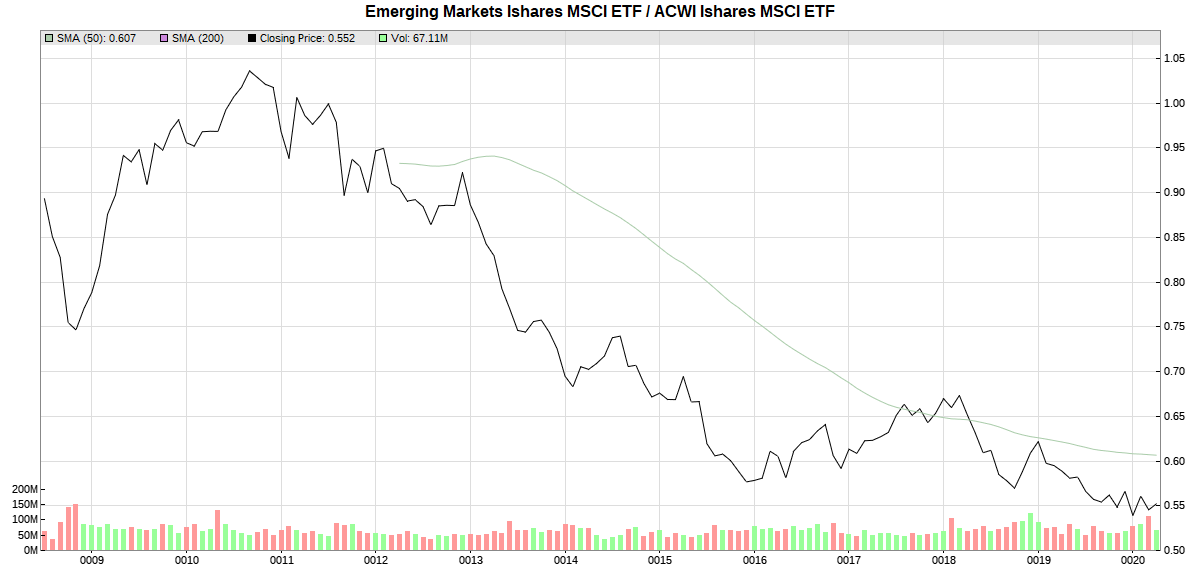

Finally, on a slightly longer timescale, emerging markets should react positively to higher commodity prices and higher inflation. They have been underperforming developed markets since 2011. This should coincide with a reversal in the dollar.

Project Zimbabwe?

These are extraordinary times. Extreme fiscal and monetary policies are rolled out just as market participants are expecting very low inflation for a very long time. Given the determination of the policy makers (we will do “whatever it takes”), if they don’t succeed at first, they will surely redouble their efforts.

Other Articles on this subject

“Project Zimbabwe” by one commentator with a good sense of humor. I’m hoping Kuppy i right directionally, but not literally.

“The policy response to coronavirus: printing our way to salvation or inflation?” in the Canadian Investment Review tries to answer some key questions related to money printing and inflation

“A CRAZY BUT LOGICAL CALL FOR STAGFLATION” [PDF] a discussion of what levels of inflation are priced into markets (hint extremely little just as policy is turning hyper stimulative)